The Shan-ni People of Indawgyi

Myanmar Regions and States

One of the most common things we hear from visitors is that they are not sure whether Indawgyi Lake is a predominantly Christian or Buddhist area. There are more than a few reasons why this can be confusing. Indawgyi Lake is located within Kachin State so most people assume that people around here are Kachin and usually Christian. However, for many parts of the state this is not true. Put simply, most of the people at Indawgyi are not Kachin, but Shan-ni (also known as the Tai Laeng*), a subgroup of the larger Shan-gyi (big Shan) who live in Shan State and although the Shan-gyi and Shan-ni are related, the Shan-ni do have their own unique script and culture.

To begin with, it is important to remember how is Myanmar divided. There are seven regions with dominant Bamar ethnic group populations and seven states which derive their name from the largest ethnic group within the state. Hence the name Kachin State.

However, the whole concept of these classifications is misleading at best particularly in regards to the Shan People. The historic Shan Kingdoms stretched from the borders of India throughout present-day central and northern Myanmar and into Thailand. There were and are Kachin People around Indawgyi, but they primarily lived in the mountains and always had smaller populations whereas Shan people spread across the entire region.

Where the Shan-ni Live

So why is there only one Shan State today with the rest of the various Shan groups spread across the country? The simple answer is colonialism. The Shan States were some of the last parts of Myanmar to be colonized during the nineteenth century. As Myanmar gained its independence, the British advised separating the Shan populations across several states so that it would be easier for the Burmese central government to administer the northern portion of the country. Shan State was created, but the other Shan groups became minorities in Kachin State and Sagaing Region.

The 1950s and early 1960s were turbulent times in Myanmar. Many ethnic groups across the country were forced into accepting the Union and surrendering their arms or rebelling. An effective establishment of Buddhism as the state religion of Myanmar started with U Nu’s State Religion Act that was passed in 1961, and Ne Win used the civil unrest caused by this law with non-Buddhist minorities to justify his military coupe in 1962. He quickly undid many provisions of the act, but informal measures to support a national Buddhist agenda persisted. From this, the Kachin Independence Organization had been formed and fighting that still continues today began breaking out in Kachin State.

Shan New Year Celebration at Indawgyi

But this is not the story of the Kachin. There is a vast amount of research and focus on this ever-brewing conflict. This is the story of the Shan-ni People who have been caught between these two sides for over fifty years and have suffered abuses from both of them.

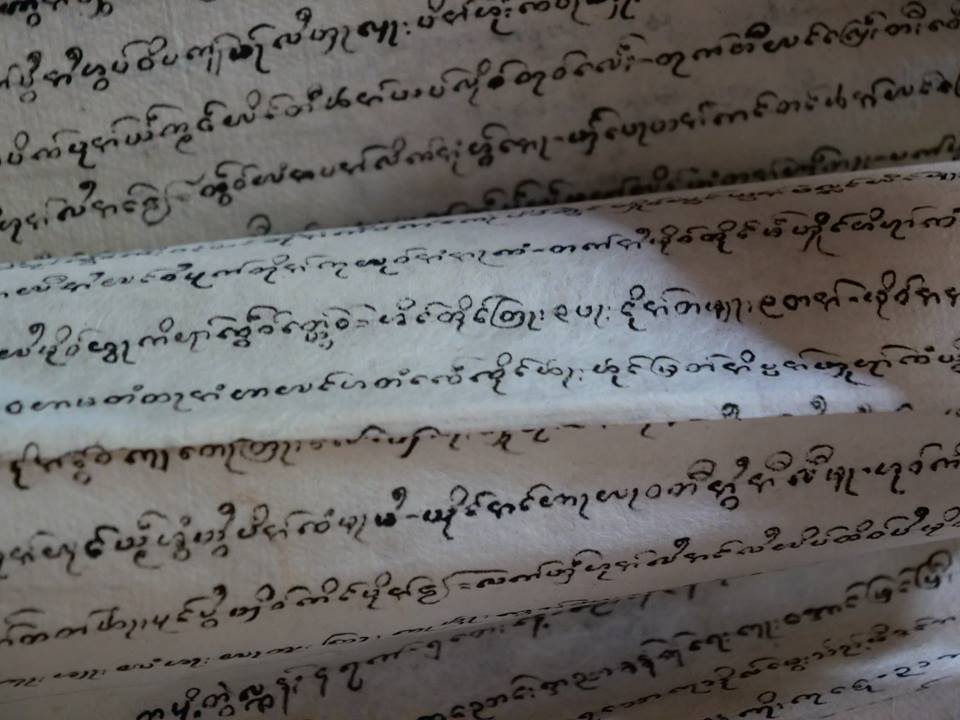

Shan-ni scrolls from Lon Ton Monastery

The Shan-ni wanted peace and during the period of independence, they gave up their weapons so that they could resume normal lives. However, throughout the 1960s and 1970s the conflict between the Kachin Independence Army and the Myanmar Army (Tatmadaw) increased. The KIA would regularly tax Shan-ni villages, forcibly recruited Shan-ni people to be soldiers and killed anyone they suspected of aiding the Myanmar government. Naturally, the Shan-ni welcomed an increased Tatmadaw presence in their home areas as a form of protection against the KIA.

This protection came at a cost, however. During this era, the Myanmar government had made the teaching of ethnic languages (and thereby culture) illegal. Around Indawgyi, where the Tatmadaw had built up a strong presence this made it virtually impossible for over two generations of people to learn their own language. If you were caught speaking Shan-ni or found with any Shan-ni documents then you were either put in jail or killed. Many historical texts and artefacts were destroyed and what remains is largely thanks to the monks and monasteries who kept sacred Buddhist documents along with the spoken Shan-ni language alive.

Shan-ni New Year Celebration photo from Eleven Myanmar

Today, there are only a handful of people who can write Shan-ni at the lake. Some of the older generations can speak it, but most young people cannot. This year, the government finally legalized the teaching of the language again and there are some classes now being taught throughout Mohynin Township. The damage has been done, however, as many young people struggle to connect with a history that was nearly erased for fifty years.

Currently, there is a small renaissance of Shan-ni Culture and publications like the Voice of Shan-ni along with cultural festivals are positive signs of change. There was a generation of people who kept this culture alive from monks to teachers and farmers and Face of Indawgyi is working with them to boost the visibility of Shan-ni Culture in a variety of ways both around Indawgyi Lake and to a bigger audience.

We are currently hosting a linguist to create the first academic study of Shan-ni which will be used as a framework for more language classes. In addition, we are working with villages to create different types of signs around the lake written in Shan-ni, Burmese, and English to help bring the language back into daily life. Finally, we have a begun a video archive of stories, songs, and histories that will all be accessible online so that future generations can hear and understand the lives of their ancestors in their words and their own language.

*Shan-ni is a Burmese corruption of the name "Shan." In their language, they call themselves Tai Laeng, however, most people use the term Shan-ni and Tai Laeng interchangeably. That said, generally Shan-ni is said more frequently in conversation which is why it was the preferred term in this blog piece.